“Impossibility of an island”

Why Charles Fourier was so right and so wrong at the same time

I have felt so many times that the choice of this era

is to be destroyed or to morally compromise ourselves

in order to be functional — to be wrecked,

or to be functional for reasons that contribute

to the wreck.

— Jia Tolentino, “Trick Mirror”

Living the dream

Here are a few tech companies: Airbnb, WeWork, and Tinder. Airbnb’s product is the dream of open borders and exciting experiences all over the world, of kind hosts and responsible, appreciative guests. WeWork’s product is the dream of working on the things you love in beautiful spaces with an option to create spontaneous creative collaborations with like-minded individuals and companies. Tinder sells a bottomless pool of romantic connections and friendships presented as an endless catalog of personal cards with short descriptions.

The narratives of these companies neatly wrap in a cycle when one visits their career websites. On these pages, the companies are pitching themselves as places to work. We’ll get into more detail on these messages later, but the general topics are meaningful mission, work in an inclusive collective of passionate professionals, personal growth, comfortable conditions, and tools to do the job. Along with the freedom to travel, produce, consume, and simply live your best life.

This world is familiar to me, as I work in a company that operates on the same tenets. So, discovering it on the pages of Fourier’s writings dating way back to the 19th century was jarring and intriguing. I also happen to know that the pieces of Fourierian utopia don’t exactly work the way he imagined them to work. While he imagined that attractive work, clean workshops, and amorous freedom would come from his beloved “Harmony,” it very much came out of the “Civilization,” he despised so thoroughly.

So even though he was uncannily precise in his description of some pieces of a future utopia, he still reads as a madman, but admittedly a bit less of a madman than I imagine he sounded almost 200 years ago. And I have a hypothesis about where this break from reality stems from. We’ll examine the areas the way Fourier imagined them to work, how they actually work, and how come he missed by such a margin.

Travel and shared living

Quote from Airbnb’s job portal:

Live your best life. There’s life at work and life outside of work. We want everyone to be healthy, travel often, get time to give back, and have the financial resources and support they need.

Quote from Fourier:

In production by the parceling out of agricultural and domestic functions and the subdivision into families. For the family is the smallest, the most inefficient and most wasteful of groups: the family system often requires one hundred workers to do a job which might be done by a single individual under societary management.

Fourier was frustrated with the inefficiencies of the system of individual self-sustaining households the “Civilization” created, and thus can be considered a prophet of two somewhat contradicting economic forces of our time: huge concentrated production and distribution hubs vs. the idea of “sharing economy.”

While Fourier’s is a fair note, it consequently branches into two trends that work against each other. It is so because Fourier actually does not provide a practical blueprint that considers actual trade-offs that come with changing the order he was unhappy about. He may think he does, but an elaborate fantasy that encompasses the whole world all at once is not it.

But when the practicality guided by one or the other sets of principles meets the seed of this idea, we end up either with concentrated production and retail hubs of monopolies and oligarchies that depend on the scale of production or with a conscientious consumption of the sharing economy brought to preserve the resources and tamper the overproduction.

Airbnb and a bunch of others are fruits of both of these trends. The more efficient handling of the resources provides a surplus of such a luxury as attractive and affordable housing; the sharing economy opens these apartments’ doors so not only the owners can enjoy them. So, while it may seem that due to these two trends meeting together at one point, Fourier was entirely correct, he wasn’t. We did get to this point, but not the way he envisioned.

What we have is still the product of the “Civilization” because of how their operation is supported. Leaving aside the broader consideration of the market forces that motivated the building of these products and the funding that enabled them, we can look at their day-to-day operation and see it’s way off Fourier’s utopia course.

One of the most elucidating illustrations would be the way the security services of such companies work. These are teams of ex-law enforcement/intelligence officers. They handle and contain criminal, violent incidents in a way that doesn’t hurt the brand. They sweep under the rug potential scandals.

In other words, for the shared housing utopia to work, someone has to pay for it, and someone has to be willing to dirty their hands. Fourier would probably argue that this is exactly the perversion of nature and the vices of “Civilization” we must get rid of. But to me, it seems he missed the reality of how power flows in nature, and his claims of discovering some fundamental laws are baseless.

Attractive work

Quote from WeWork’s job portal:

Leading with purpose. More than just building spaces where businesses can do their best work, we’re dedicated to caring for our people and the environment.

Quote from Fourier:

By working in very short sessions of an hour and a half, two hours at most, every member of Harmony can perform seven or eight different kinds of attractive work in a single day.

The other noble piece of Fourier’s picture is the desire to make labor attractive. His belief in the importance of work made him concerned about many aspects of work — the spread of “labor parasites” and conditions of the actually productive working class.

And now, there we have it, a class of workers who are offered very attractive conditions to work. Until recently, it was the beautifully designed offices with snacks and entertainment, and now it’s the ability to work from home or anywhere on the planet. Plus, the workers are endowed with some flexibility about the activities and projects they are willing to engage in. And a significant portion of them is rewarded with shares of the enterprise they associate with.

As with any other piece of utopia, there are caveats. First, at the current level of technological development, it all mostly means that the unpleasant and demeaning work is not eradicated but pushed down the line to those who aren’t lucky enough to escape it. Second, again, someone has to pay for all of this, and WeWork specifically is the leading example of the issue.

The company's founder was very vocal about his vision of the complete life cycle utopia he wanted to build; the pockets of his backers took a hit for that. Not to go into too much detail, but while WeWork is still a functional business, it has never been profitable since the day of its inception. Who’s paying for it? Well, future generations will. And with the current uncertainty in the intellectual labor market, it just goes to show how this optimistic utopian approach is unsustainable. Things happen, and rigidly designed stained glass pictures of the perfect world readily shatter.

That’s another shortsightedness on the side of Fourier — the infinite abundance mindset and the assumption that things can be figured out once and will work forever after. We’ll try to uncover what stands one level deeper behind this, but for now, let’s highlight that it is connected with the lack of understanding of how hard it is to win a piece of order from the chaos of nature.

New amorous life

Quote from Tinder’s job portal:

Create real connections. We're doing something meaningful- helping people find their people. You'll be proud of the experiences you help create for humans all over the world. Take any modern tech company.

Quote from Fourier:

Let us confine ourselves to pointing out that in love as in commerce the progress of civilization is merely progress in social falsehood.

The case for this is especially curious because the lack of empirical knowledge on Fourier’s side shines in particular. Somehow, musings on more abstract topics like politics and economy pass with greater ease. But when things get personal, it’s really hard to take serious advice from someone unfamiliar with the sacrifices and vulnerabilities of building a real connection with another person or group of persons.

However, again, one of Fourier’s designs is implemented to a tee, at least on a superficial level. We really do have catalogs of neat little cards with people's faces, and theoretically, we can choose people we’ll be able to connect with. But in practice, it does not function the way Fourier would be pleased with.

There’s a host of problems with this piece of utopia. For one, the inherent manipulativeness of the product, coupled with the misalignment between the provider's interests with at least a portion of its consumers. Tinder wants you never to settle and keep paying, so their algorithm better not serve you the perfect match. If your goal is to start a family, it seems that the only incentive scheme that’d work is for the couple to pay Tinder for each month they’re staying in the relationship.

The other issue is that this kind of interaction is only available in societies that have relaxed their moral codes significantly, and it is only possible in affluent societies with functional states and developed institutions.

So, to be fair, Fourier warns his readers that this whole thing is connected and only works when all the pieces of “Civilization” are replaced with those of ”Harmony.” But the charge of not bridging the chasm between the current arrangement and the perfect future still stands.

However, maybe it’s the only area where Fourier was pretty much right about the first steps; the emancipation of the vulnerable classes was necessary and one of the most reasonable first steps to take. And yet, this was only possible through a significant power struggle, which Fourier was so averse to.

Before we move on, I’d like to highlight that the particular brands I picked are unimportant. Those are just familiar brand names used as examples for broader categories of enterprises and the dynamics of their workings.

An outlet in the wall

In very Fourierian fashion, I’ll attempt to bring my “charges” against his doctrine to one root cause. So far, we have:

- Unsupported claim for the infinite abundance. While yes, it’s true nature contains multiples and multiples of resources needed for humanity’s existence, the trick is in extracting those in a consistent and sustainable manner, and none of Fourier’s blueprints outline the realistic ways to get to it;

- And that is because much of his speculations weren’t backed up by any empirical knowledge. For a lot of topics he aimed to contribute, he didn’t have enough of a grasp, and attempts to think these limitations away only make the matter worse;

- The refusal to accept the dynamism of natural life, nothing in the realm of matter works like this: figure it once, and it’ll never break.

While Fourier boasted that he was the one who got the laws of nature, he actually missed the fundamental components of all things living: competition, struggle, and power. In civilization, he saw the perversion of nature, which leads us away from the humanistic ideal, but I argue it’s not the case. It is the natural way to deal with elements to build things that divert the danger and help us harvest the resources. Power is one such element, and civilization is our system to deal with it.

Refusing to accept the fact that we need such a system is a failure to see what Fourier claimed he saw. His “natural” way of doing things was never actually implemented, and the “perverse” way of civilization is the one that has always been. Even in the framework of Fourier himself, If God/Nature is so powerful, merciful, and omniscient, it’s just parsimonious to assume that things are already in order and go exactly how it was supposed to.

Thinking against the mainstream is often the most noble enterprise, but it loses all its charge once completely disconnected from whatever passes for the reality of the moment. Turns out, a gradually built sophisticated power distribution system is more capable of delivering the desirable outcomes than confidently pointing the finger and exclaiming, “Go there because I just know.”

With a little license, I’ll attempt to describe what I picked up as potential reasons for that to be the case.

Logic of the fantasy. Cycle of insecurity

I want to contextualize Fourier's spurious confidence. At the risk of psychologizing too much, I’ll attempt to describe how I see it working. And since it’s a cycle, it’s unimportant at what point we start.

We’ll start with this stark lack of real expertise that Fourier shows in his descriptions of minutia; while it may have been the aim of these to impress the reader with the depth and scale of thought, what it really shows is a complete lack of contact with the subject matter, be that architecture, managing a collective of people or design of the menu. The lack of real expertise leads to simplistic ideas, to the overall primate of “common sense,” and the belief that if you have the most relaxed grasp of a couple of pieces in the picture, nature will draw in the rest. Simplistic ideas lead to the conviction that one person can devise the plans for everything because it’s, well, simple. If you’re convinced everything can be designed single-handedly, you don’t need others to collaborate with. From the inside, this leads to self-inflicted isolation. From the outside, it leads to rejection and ridicule, which breeds a degree of resentment and insecurity, which leads to an aversion to engaging with things and accepting pushback and feedback, which prevents gaining expertise. And thus, the cycle is complete.

The strict routines he tended to stick to are circumstantial evidence that this is how he approached not only his ideas but life in general. All these long lists of personality types and cuckold classes summoned to show the command of the matter read as futile attempts to shield from the unstable environment instead of facing its irregularities.

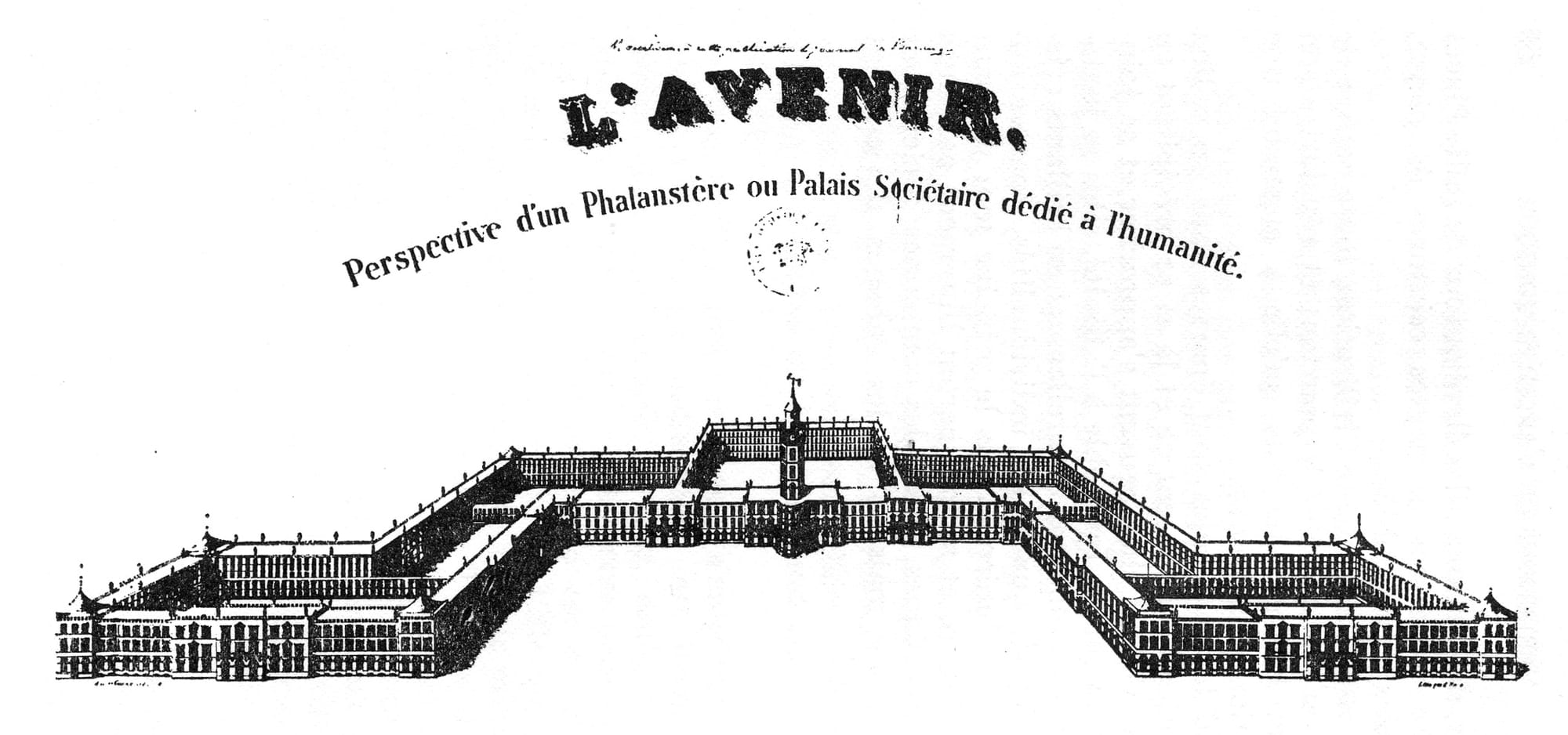

Ironically enough, precisely because parts of Fourier’s vision had been realized before our eyes, we can now charge him with utopianism, with building a place that doesn’t exist and can never be. Fourier’s Phalanxes are all built on an island no one knows how to get to, while our attractive workshops with cooperative friends are here, enmeshed in our lives and rooted in the soil of ugly things that must be dealt with.

Personal note and conclusion

It may seem that I’m inconsiderate of the actual contribution to Fourier’s thought. But it’s quite the opposite; I’m fascinated with the parts he got so right more than 200 years ago, and I expect some things we’ll get to us in centuries to come. And he was a major inspiration behind some positive change. I’m just saddened that the timidity of action so severely crippled such courage of imagination.

Personally, I resonate with his frustrations and fears a lot. To the point that I’m open to the idea that my assigning shortcomings of his writing to fears and insecurity is just me projecting my own issues onto his texts. Everything is out of whack, unjust, and poorly designed; of all the authors we covered, he’s on my short list of the ones “I click with.”

It’s an achievement to venture so far from convention alone. But to gather a group and work together to bring the vision back to reality is way more impressive. Even Fourier himself would confirm people like working in groups. His group hadn’t been found or rather never managed to consider the reality of constraints and trade-offs they must deal with. You can only build something if you're grounded and not oblivious to adversarial forces.

The refusal to engage with the constructive and oppressive aspects of power leads to these outcomes. If the idea is not supplied with practical roadmaps for execution, it’s vulnerable to being co-opted and delivered in a way that is far from intended.